Satisfying a 31-Year-Old Karaoke Dream

I was talking to my dad about setting up karaoke for our family’s New Year’s Eve party. He asked if there was any software that could do real piano karaoke, where the player piano would accompany you while you sang. He’d dreamed of this for 31 years, ever since we got the piano. A quick Google search turned up nothing. “I can build that,” I said.

24 hours later, I had a working app. Here’s how I did it.

The setup is a Yamaha baby grand with a Disklavier controller, which is Yamaha’s system for recording and playing back piano performances via MIDI. The keys physically move, the hammers strike the strings, and you get a real acoustic piano sound synced to whatever MIDI data you feed it. The solenoids used to power the piano often share a combined circuit, so sending too many commands will overload the power delivery, and you get some comical results

The missing piece was software to parse karaoke files, display lyrics, and route the piano track to the player piano while playing the backing instruments through the karaoke speakers.

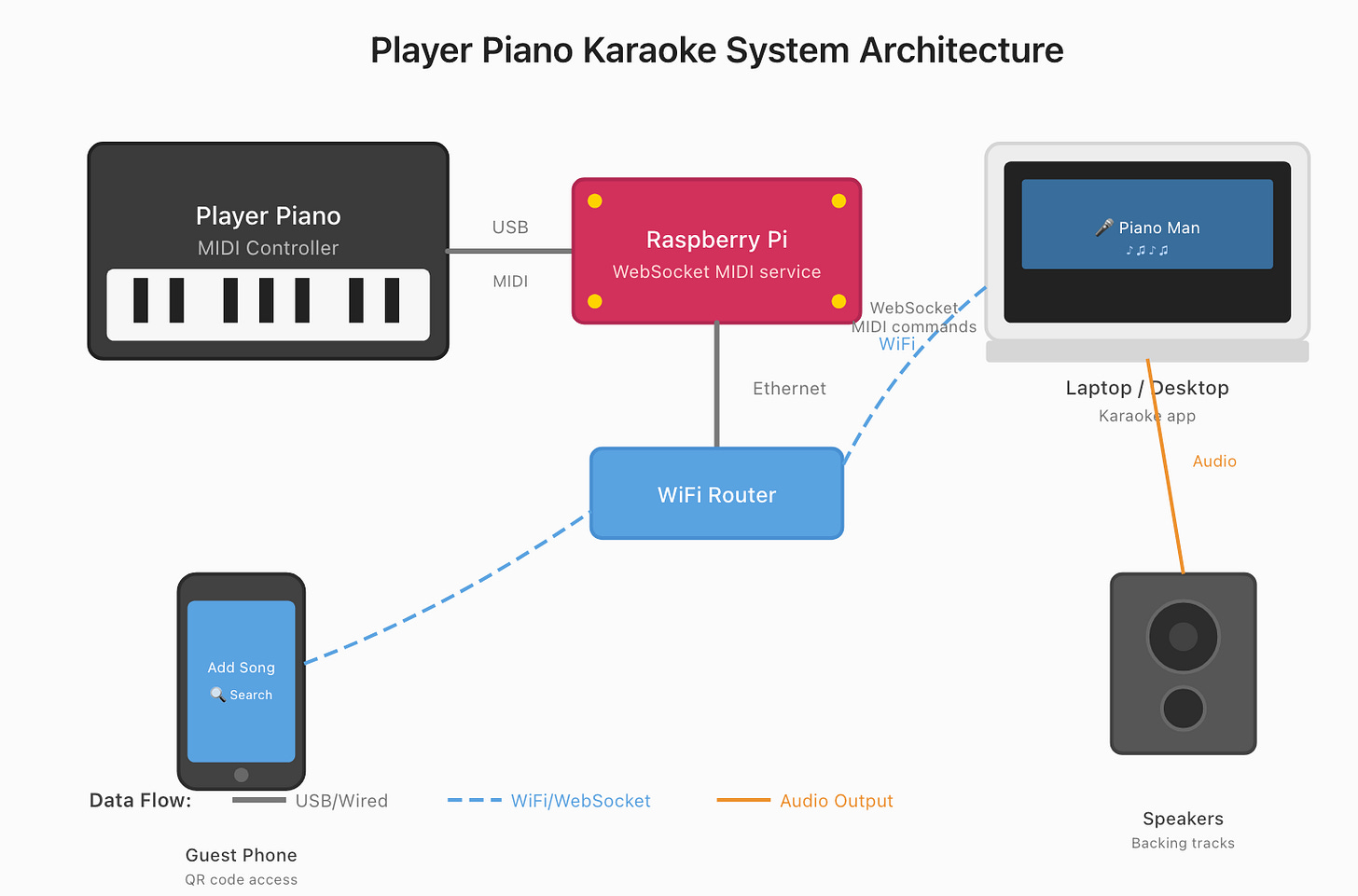

The Hardware Connection

My first attempt was to connect the piano’s control unit as a network MIDI device. This didn’t work. The controller doesn’t support network MIDI, and reverse engineering the proprietary network protocol seemed like a rabbit hole I didn’t want to go down. USB turned out to be a tractable path, at least initially.

Installing the USB-MIDI Driver

On macOS, you need the appropriate USB-MIDI driver for your player piano. For Yamaha devices, download it from their support page:

https://usa.yamaha.com/support/updates/usb_midi_driver_for_mac.html

After installation, the piano appears as a MIDI device in your system.

Configuring the Controller

The piano settings matter. Here’s what finally worked for my setup. You need to use the Yamaha remote that comes with the Disklavier, click Setup, go to MIDI, and set the following settings (Use the ON/OFF buttons to toggle):

MIDI IN Port = USB

Piano Rcv Ch = 01

MIDI IN Delay = ON

MIDI OUT Port = USB ← THIS IS THE FIX

MIDI OUT = KBD Out

KBD OUT CH = 01

Local = ONThe critical setting is MIDI OUT Port = USB. Without this, the piano wouldn’t respond to incoming MIDI commands at all. I spent longer than I’d like to admit figuring this out.

Testing the Connection

Once configured, you can verify the connection with a simple script that cycles through the keys that I wrote: https://github.com/DavidWatkins/midi-karaoke/blob/main/scripts/midi-test-keys.js. When this runs successfully, you’ll hear the piano play a chromatic scale from C2 to C7. The keys physically depress. It’s a satisfying moment.

❯ node scripts/midi-test-keys.js

MIDI Key Test

Port: [Your MIDI Device]

Channel: 0

Notes: 36 to 96

Velocity: 80

Delay: 300ms

Connected! Sending notes...

Playing: C2 (MIDI 36)

Playing: C#2 (MIDI 37)

...

Playing: C7 (MIDI 96)

Done!Going Wireless: The Raspberry Pi Solution

The USB setup worked, but it meant keeping a laptop physically tethered to the piano. I wanted something more permanent that wouldn’t force me to navigate through the room just to tend to the computer hastily connected to the piano. Sometimes the best thing to do when working on these projects is to step away from the keyboard, get a nice lunch, and on the drive over, it’ll click. Put a small computer next to the piano, connect it via USB, and expose the player piano as a network device. I used a Raspberry Pi, but any simple computing solution would work.

My first attempt used rtpmidid to create a standard Network MIDI device that would appear in macOS’s Audio MIDI Setup. This failed spectacularly. The MIDI packets were getting corrupted in transit, and somehow every note was being routed to E5 regardless of what I actually played. I tried Ravelox MIDI as an alternative implementation and hit the same issue. Something about the Network MIDI protocol stack was mangling the data.

The fix was to abandon the Network MIDI entirely and use WebSockets instead. The Raspberry Pi runs a small Python web service that accepts MIDI commands over WebSocket and forwards them to the piano via USB. It’s not as elegant as a proper Network MIDI device (other apps can’t discover it automatically), but it works reliably.

The Pi can also run FluidSynth to synthesize backing tracks and broadcast over AirPlay, but I don’t recommend this. AirPlay adds 1.5-2 seconds of latency, which makes the backing tracks comically out of sync with the piano. For now, the karaoke app handles its own audio synthesis locally, which keeps everything tight. If there is demand for connecting a Bluetooth speaker to handle the synthesis rather than AirPlay, I could revisit it, but it seemed more gimmicky than it was worth.

The result is a self-contained system. The Pi lives next to the Piano, connected via USB and Ethernet (or WiFi). The karaoke app on any computer in the house can connect to it wirelessly. No cables strung across the living room.

The Raspberry Pi code is available at: https://github.com/DavidWatkins/midi-piano-pi-server/ and the walkthrough of the physical hardware stack is here:

Installation is a single command:

curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/DavidWatkins/midi-piano-pi-server/main/install.sh | bashA Brief History of KAR Files

In order to get lyrics synchronized to the piano, I need a stable format that contains syllable-level information synchronized with the instruments. Back in 1993, the KAR format was developed by Tune 1000 Corporation for their product Soft Karaoke. It’s an extension of the standard MIDI file format. A KAR file is essentially a Type 1 MIDI file with lyrics embedded as text meta events, synchronized to the music. The format uses special tags: @KMIDI KARAOKE FILE identifying it as a karaoke file, @T for title, @L for language, and so on. Syllables are stored as individual text events timed to when they should be sung, with spaces and line breaks encoded as special characters.

The format had legs. Roland, Technics, and other keyboard manufacturers adopted variations of it for their arrangers. A community of hobbyists emerged, sequencing MIDI tracks and painstakingly entering lyrics syllable by syllable. The files were small enough to share on dial-up connections and bulletin boards.

But KAR files have largely faded from mainstream use. The shift happened for a few reasons. First, MIDI synthesis sounds dated compared to recorded audio. Modern karaoke services like KaraFun use MP3+CDG (an MP3 paired with a graphics file for lyrics) or simply stream pre-recorded backing tracks with video. The audio quality is incomparably better. Second, licensing became more formalized. Services now pay for rights and re-record tracks in studios rather than relying on fan-sequenced MIDI. Third, convenience won. Why hunt for KAR files when you can pay $7/month for a streaming catalog of 50,000 songs? (Obviously, so you can have your player piano play alongside your singing, duh)

For most people, KaraFun or a similar service is the right answer. But those services cannot drive a player piano. The piano needs MIDI data, actual note-on and note-off events that tell which keys to press. An MP3 is just audio. A MIDI file doesn’t contain lyrics. This is why KAR files still matter for this project: they’re one of the few formats that contain both the musical performance as playable MIDI and synchronized lyrics.

One idea I had as a potential follow-on project would be to extract the piano/harpsichord/keyboard/etc. track from an arbitrary MP3 and turn it into MIDI. Recent research in automatic music transcription has made significant progress here. MT3 [1] uses a transformer architecture to transcribe arbitrary combinations of instruments from audio to MIDI-like token sequences. Pop2Piano [2] takes this further, generating piano covers directly from pop music audio without requiring separate melody and chord extraction. A pipeline combining source separation (like Spleeter or Demucs) with instrument-specific transcription could work well for extracting just the piano track. I’ll consider this for a future version, but for now, KAR files met my needs.

Expectation Versus Reality with a Player Piano

KAR and MIDI files contain multiple tracks: piano, bass, drums, strings, and so on. Each instrument is assigned to a MIDI channel (0-15).

My player piano only plays notes on channel 0 (or channel 1 in 1-indexed notation). Send a note on channel 3, and the piano ignores it. But here’s the confusing part: the control unit has a built-in MIDI synthesizer. So when I first loaded a KAR file and sent all channels to the piano, I heard music, but it sounded like a video game soundtrack. The synthesizer was playing all the instruments through the piano’s speakers, but the actual keys weren’t moving.

The fix is to identify which track contains the piano part, remap those events to channel 0 for the player piano, and play everything else through a software synthesizer on the laptop. This gives you a real piano for the melody and accompaniment, with backing tracks coming through your speakers.

Another issue I ran into is that splitting audio between two sources creates a timing problem. The player piano adds a 500ms delay to all incoming MIDI commands. There’s supposedly a way to disable this, but then the player struggles to keep up with rapid note sequences. The delay exists for a reason.

The solution is to delay the laptop audio and lyrics display to match. The UI now accounts for this offset, keeping the backing tracks and lyrics in sync with the physical piano. Getting this right took some iteration. When the timing is off by even 100ms, it feels like the band is drunk.

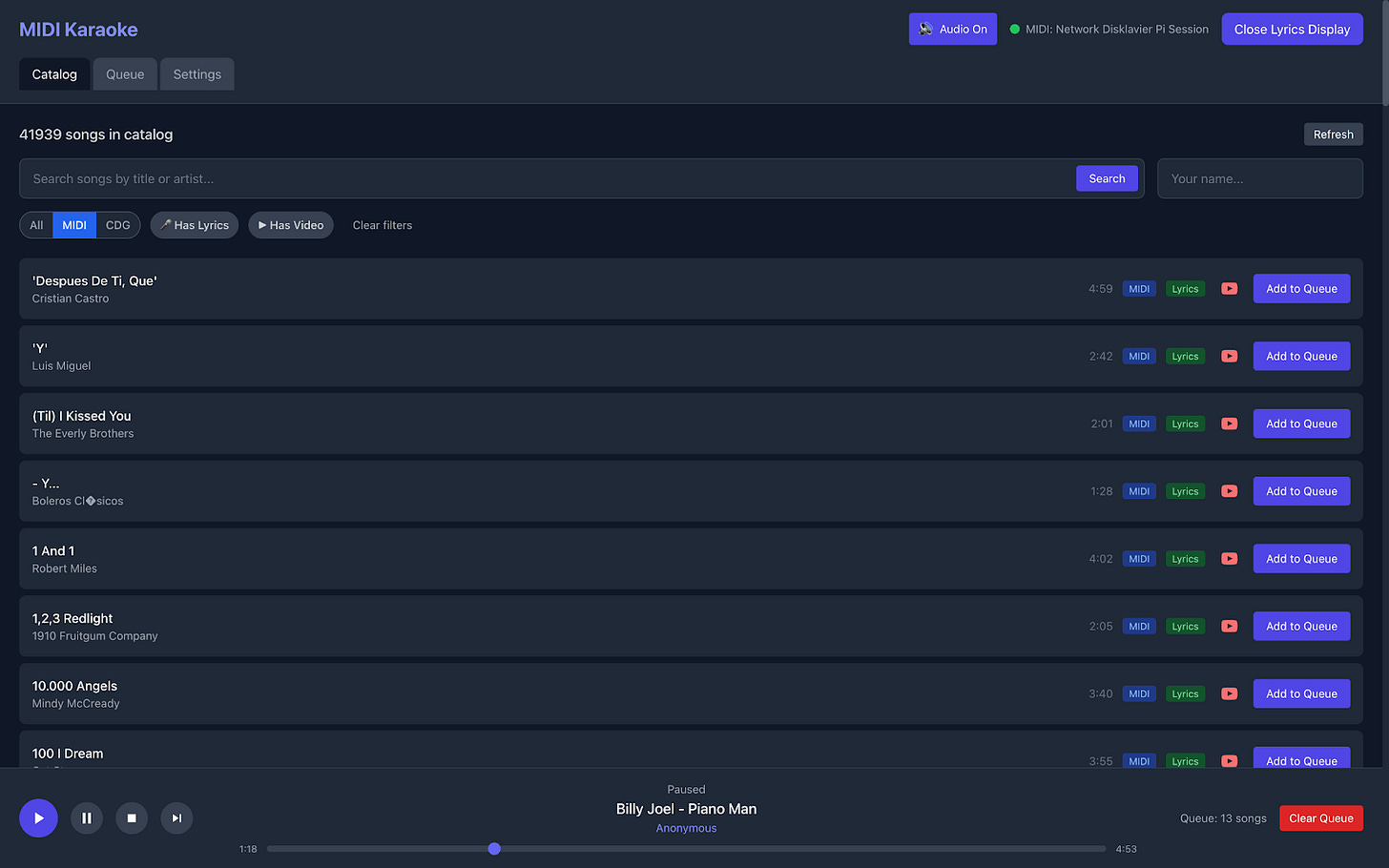

The Software Architecture

The Karaoke app is an Electron application built with TypeScript, Vite, and Tailwind. The key libraries are:

JZZ for MIDI I/O (if using a direct USB connection via the karaoke app)

@tonejs/midi for parsing KAR/MIDI files

Tone.js for software synthesis of the backing tracks

WebSocket client for communication with the MIDI Pi Server

The architecture splits the MIDI stream: piano events go to the player piano (either directly via USB or through the Pi’s WebSocket), everything else routes to Tone.js for local playback. The lyrics are extracted from the KAR file’s meta events and displayed in sync with the music.

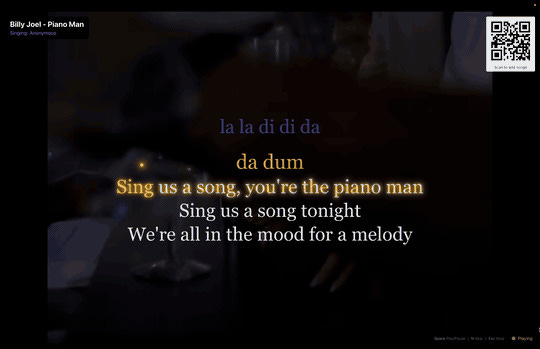

The interface includes a song queue, search, and a web portal for adding songs. A QR code on the screen lets guests scan and submit song requests from their phones. I even added a WiFi QR code so family members who are not on the network can connect and access the web server. At a party, this means anyone can queue up their song without touching the main computer.

For lyrics display, you can choose between a scrolling view or a bouncing ball mode. Getting the ball to arc naturally between syllables took some back and forth with Claude Code. The initial implementation moves the ball directly over each syllable, depriving the audience of that classic ‘90s karaoke vibe. As soon as I asked Claude how it had implemented the animation, it became clear I had explained the instructions incorrectly. Asking it to explain the implementation to me was a nice shorthand from having to completely dive into the animation code, and the result was a nice bouncing ball over each lyric.

You can also set YouTube videos as backgrounds for individual songs. The video plays muted behind the lyrics while the KAR file provides the actual audio. It’s not perfectly synchronized, but it’s surprisingly close, and having the music video playing while you sing adds to the atmosphere.

Soundfonts

Here’s something I didn’t anticipate: the choice of soundfont dramatically affects the karaoke experience. Since the piano part goes to the player piano, the soundfont only affects the backing tracks (drums, bass, strings, etc.). But those backing tracks set the entire mood.

My first attempt used MusyngKite, a commonly recommended free soundfont. Everything sounded like a video game soundtrack. The electric guitar, in particular, was awful, thin, and synthetic in a way that clashed terribly with the real acoustic piano. Karaoke is supposed to feel like you are singing with a band, not a Nintendo Famicom (not to bash Karaoke Studio stans).

I tried FluidR3 next, which is larger (~140MB) and more commonly used in professional applications. This sounded way better. The instruments had more body, and the backing tracks no longer fought with the acoustic piano for attention.

Then I found the General Montage SoundFont by Daindune, which weighs in at about 1.5GB. It’s built from samples from Versilian Studios, Freepats, and other sources, with 128 instruments and eight drum kits. This one sounds significantly better than FluidR3. The instruments have more presence and realism, which matters when they’re playing alongside a real acoustic piano.

Here is a comparison using “Let it Snow” (a royalty-free classic):

FluidR3:

General Montage:

The difference is most noticeable in the brass and strings. General Montage has warmth, where FluidR3 sounds thin.

The app ships with FluidR3 and MusyngKite as built-in options, and lets you load custom SF2 files at runtime to try them out mid-session. If you want to go down this rabbit hole yourself, the Internet Archive has a collection of 500 GM-compatible soundfonts worth exploring. The quality varies wildly, but it’s a good way to find something that matches your taste and your song library.

Finding KAR Files

KAR files aren’t as easy to find as MP3s, but there are several repositories worth knowing about:

midkar.com has over 43,000 MIDI and KAR files, organized by genre

freemidis.net offers around 6,400 free MIDI and karaoke files

karaokeden.com has free MIDI karaoke in multiple languages

The quality varies. Some files have well-sequenced piano parts that translate beautifully to a player piano. Others have the piano buried in a mix of instruments or missing entirely. There was something deeply unsettling about the guitar being remapped onto the player piano in Elvis’s Can’t Help Falling In Love With You.

Try it Yourself!

The first song I tested was, of course, Piano Man. It worked phenomenally well. There’s something special about Billy Joel’s piano part played on real hammers and strings while you belt out the lyrics. A real piano captures the dynamics in a way that a software synth never could.

The Beatles - Yesterday

Billy Joel - Piano Man

Chicago - 25 or 6 to 4

Both projects are open source:

MIDI Piano Pi Server (The Raspberry Pi Service):

https://github.com/DavidWatkins/midi-piano-pi-server/

MIDI Karaoke (The Electron App):

https://github.com/DavidWatkins/midi-karaoke/

Precompiled applications for macOS, Windows, and Linux are available in the releases. If you have a Disklavier or any MIDI-enabled player piano, I’d love to hear if it works for you.

The Beatles - Let It Be

After 31 years, my dad finally has his synchronized karaoke system. Watching him sing along while the piano plays itself was worth every hour of debugging MIDI channels and soundfont hunting.

Lessons for Robotics

I made the player piano do something no one had made it do before, a new technological achievement, humble as it is. And Claude Code alone could not complete this project. Interfacing with different compute systems, plugging cables together, and debugging subtle timing issues - all of this requires high-dimensional perceptual input and high-dimensional long-horizon goal-directed output. The amazing thing about humans is our ability to dream up a goal, and then dream up a technical solution allowing us to achieve the goal, pushing subgoals and subgoals on the stack, and popping them back off to satisfy my Dad’s whimsical request.

References

[1] Gardner, J., Simon, I., Manilow, E., Hawthorne, C., & Engel, J. (2022). MT3: Multi-Task Multitrack Music Transcription. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.03017

[2] Choi, J. & Lee, K. (2023). Pop2Piano: Pop Audio-based Piano Cover Generation. In IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 1–5. https://github.com/sweetcocoa/pop2piano

David Watkins is a Research Lead at the RAI Institute, where he leads teams working on robotic manipulation and foundation models. When not collecting robot demonstration data, he builds karaoke systems to fulfill 31-year-old family dreams.

Disclaimer: This is an independent project and is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or sponsored by Yamaha Corporation or any other company mentioned. All product names and trademarks are the property of their respective owners.